1.4 Early Economic Prosperity under Christian IV

Meanwhile the economy saw golden times through record export of grain to the south, and the new Baltic Sea shipping, which was dominated by the Dutch, brought additional prosperity to Denmark. Through her control of the Sound (both on the Danish and Swedish side) Denmark was the dominant presence in the region. Sweden then conceived a plan to free itself from the grip of Denmark. This led to a few wars between the two nations, with Sweden seeking the help of Russia. Christian IV (1577-1648) [1] even committed his nation to the gruesome Thirty Year’s War. Albrecht von Wallenstein (1583-1634) punished Denmark’s unhappy participation in this conflict with a crushing defeat and the occupation of Jutland. The Swedes followed Wallenstein’s example by occupying the provinces on the Sound and by unilaterally eliminating the Sound Toll, with the Dutch following their example [2]. In 1657 the Danes took revenge for this slap in the face by declaring war on Sweden while that country was busy intervening in Poland and expanding its hegemony. However, the Swedes kept the upper hand in part because they attacked Denmark from its provinces in Northern Germany, invaded Jutland, crossed the frozen Little Belt (between Jutland and Fionia, then the Great Belt to the southern Danish islands and Sealand. It was at the following peace-treaty in Roskilde that the Sound became Danish-Swedish border [3]. However, the Dutch could no more tolerate a Swedish than a Danish monopoly and, aided by Brandenburg and Polish troops, compelled both parties to accept the Peace of Copenhagen (1660), which broke open control of the Sound. From then on the slogan was ‘the keys to the Sound lie in Amsterdam’. As a consequence the Danish-Swedish wars had come to an end for the time being.

Despite political conflict and war, Denmark enjoyed a time of glory from 1600 under Christian IV, which found its most marked expression in architecture and urban construction. However, the prosperity was inequitable and the gap between rich and poor became a gaping chasm. Led by the king, the nobles now took over the entire country, with the people subjected to a system of strangling servitude. The burghers still tried to secure a modest measure of prosperity by engaging in trade independent of the merchants of Lübeck. Although this appeared to work out for some time, they increasingly ran into the Dutch, who frustrated their efforts. They lacked the capital and experience needed for self-defence. Only the burghers of Copenhagen still played a significant role in the struggle between ruler, nobility and people at the beginning of the 17th century.

This political constellation came to an abrupt end in the autumn of 1660. The reason for this was the disastrous economic state of the nation around 1657-1660 as a consequence of the lost war against Sweden, whereby Denmark lost nearly a third of its total territory (all old provinces on the Scandinavian mainland to the east of Oresund ). At the same time the Swedes recovered the costs of the belligerencies and occupation from the already heavily afflicted population. In an attempt to get the national finances back under control after the peace with Sweden, King Frederick III (1609-1670) [4] assembled the estates general in Copenhagen in 1660. The three estates, the nobility, clergy and burghers, who together constituted a third of the population, were represented. The farmers, who made up the remaining two-thirds of the population, were not invited. The intention was that new taxation would be approved to help get the economy back on its feet. The clergy and burghers used the situation to have the hated tax advantages enjoyed by the nobility put on the agenda. In an attempt to force the issue, a plan was put forward to make the monarchy hereditary instead of elected. This move stood to rob the nobility of its power base in one blow, since the king would no longer need to make concessions to secure his election. The nobility and the state council, who were naturally much opposed to this proposal, were not able to turn the tide, not even by making all sorts of tax concessions at the last hour. Frederick III (1609-1670) then blockaded Copenhagen with troops loyal to him and forced the nobility to accept the proposition. Thus the hereditary monarchy was sworn in by one and all on 13 October 1660.

In gratitude the commoners received lucrative offices which had previously been the preserve of the nobility. Frederick III now called himself absolute monarch (1661) and forced everyone to sign his new statute. The new monarchy functioned without open unrest only because successive kings refrained from behaving like despots and made use of burgher parties which were tied to the crown in exchange for privileges and which were rewarded with property belonging to a part of the old, impoverished nobility. This eclipse of the elite again did not bode well for the farmers, who had to suffer exploitation as never before. By about 1700 the descendants of the free Vikings had become complete serves of the land.

However, the absolute monarch still craved revenge on the Swedes. His chance came in 1675, when ordered by her ally France, Sweden attacked Denmark, which was an ally of Holland. The Swedes were punished, after which the duchy of Gottorp and parts of Schleswig were taken away from them. However, France then abandoned its ally and though the nominal winner of the so-called Scanian War (1675-1679), Denmark was forced to give up everything she had won in subsequent negotiations (the Treaty of Lund).

Even then the struggle was not yet over because the Danish King Frederick IV [5] could not relinquish his absolutist delusions of grandeur. In the following Great Nordic War (1700-1720) Sweden and Denmark once again fought futile battles with great losses on both sides. The fortunes of war seemed to turn in favour of Denmark when Sweden, under King Charles XII (1682-1718) [6] was dealt a crushing blow by the Russians at Poltava in 1709 during a futile trek to the Ukraine. Now the Danes attacked Swedish possessions in Germany and forced the Swedes, who attempted to come to the aid of the Duke of Gottorp, to surrender. An attempt of Charles XII to take Norway from Denmark as revenge was frustrated in 1716 when a small Danish fleet was able to destroy a much larger number of Swedish ships. After the death of Charles XII in 1718 the war progressed slowly, to be concluded by the Great Northern Peace (1720), which established a new balance of power in the north. Sweden lost all her possessions on the Baltic Sea save for Finland. Denmark was able to appropriate the part of Holstein that had belonged to the Duke of Gottorp while Gottorp got to keep the rest of Holstein. Russia emerged as the great winner of the struggle and as the dominant regional power.

1

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of King Christian IV of Denmark (1577-1648), c. 1640

Copenhagen, The Royal Danish Collection - Rosenborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. 21-126

2

Willem van de Velde (I)

The battle in the Sound, 1658, c. 1660

Rotterdam, Maritiem Museum Rotterdam, inv./cat.nr. P963

3

Daniel Vertangen

The storming of Copenhagen on the night between 10 and 11 February 1659, probably 1659

Copenhagen, The Royal Danish Collection - Rosenborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. 7.27, cat. nr. 703

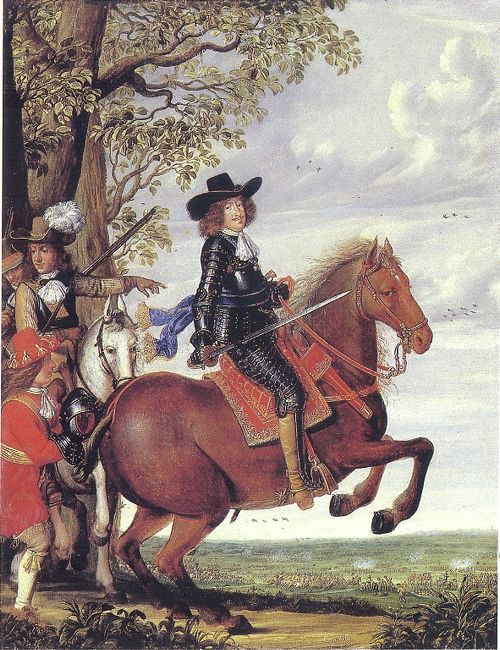

4

Wolfgang Heimbach

Portrait of King Frederick III (1609-1670) on horseback, with the battle of Nyborg (1659) in the background, dated 1660

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. A 7324

5

Hyacinthe Rigaud

Portrait of King Frederick IV of Denmark as a prince, dated February 1693

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KMS3632

6

David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl

Portrait of Karl XII, King of Sweden (1682-1718), dated 1697