1.6 France, England, Russia and Prussia Dictating Politics in Denmark

In the late 18th century the surrounding powers of England, France and Russia drew Denmark into their conflicts, much against her will and to her extreme detriment. Especially England was hostile to anyone who supported the American rebels with trade and contraband. That is why England sent its fleet under admiral Horatio Nelson [1] to Copenhagen in 1801 to force the Danes to comply [2].

In 1806 Denmark ended up between a rock and a hard place when Napoleon I [3] announced the Continental System and England responded with a naval blockade of Europe. Denmark, which was completely dependent on her shipping, especially between Norway and the Danish mainland, suffered grievously. Forced by the strangling Treaty of Tilsit of 1807, Russia joined the Continental System, so that the situation became highly precarious for Denmark. England began to manoeuvre towards a treaty between Sweden and Denmark that would have had the Danish fleet turned over to England. When the Danish began to procrastinate, England occupied the island of Zealand and bombarded Copenhagen on 2-4 September 1807 [4]. A large part of the city went up in flames and some 200 burghers lost their lives. When the English at last left with the entire Danish fleet in tow as booty (although only 15 ships-of-the-line reached England, the rest of the fleet having been lost to inclement weather or deliberate vandalism), the national humiliation was complete. The result was that the Danish government joined Napoleon, a move that was not appreciated by its own people. One consequence of this changeover was that in 1814 Denmark found itself on the losing side and was forced by the Treaty of Kiel to cede Norway to Sweden, which under King Karl XIV Johan (the former Napoleonic marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte) (1763-1844), was on the winning side. Confronted with national bankruptcy, Denmark declined to an altogether insignificant role in European power politics. Denmark kept only Greenland, Iceland and the Farøer, while a piece of West-Pomerania and the island of Rügen were traded with Prussia for the Duchy of Lauenburg and a sum of three million riksthaler which was of critical importance for bankrupt Denmark at that moment.

1

Leonardo Guzzardi

Portrait of Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805), c. 1801-1805

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. PCF14

2

Nicholas Pocock

The battle of Copenhagen, 2 April 1801, dated 1806

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. BHC0529

3

Ernest Meissonier

Napoleon at Arcis-sur-Aube near Troyes during the Campagne de France in 1814, 1862

Baltimore (Maryland), Walters Art Museum, inv./cat.nr. 37.52

4

Anonymous Denmark 1807

The nightly bombardment by the English of Copenhagen, 2,3 and 4 September 1807, 1807

However, the pressure from outside the country had still not abated. Thus Denmark became ever more involved with the problems of the North German Confederation because Lauenburg, Holstein and Schleswig were independent duchies, with King Christian VIII (1786-1848) as duke, but they were also part of the kingdom of Denmark. This uncomfortable situation was aggravated by the machinations of Prussia, Hanover and the North German Confederation, which, in its striving towards unification of Germany, began to demand a constitution for Holstein. Much against his wishes Frederick VII (1808-1863) [5], who still retained absolutist traits, agreed.

His own people, who had no revolutionary aspirations, were not at all interested. Finally it was a German in Danish employment, Uwe Jens Lornsen (1793-1838), who fanned the flames of reform in Holstein and Schleswig in 1830 and demanded complete autonomy along with a constitution. Lornsen himself was condemned to a year in prison, which turned him into a martyr for the cause. The situation escalated ever more and Copenhagen lost the ability to settle things according to its own insight. Finally, four provincial legislative meetings were convened in 1831 in Schleswig, Holstein, Jutland and the remaining islands. Although the delegates were to be chosen via a circumscribed right to vote, the universities and the clergy were allowed to appoint their own delegates and the decision of the four meetings were not binding to the king, this was nevertheless a first step from autocracy toward democracy. The representatives were largely divided into two camps, conservatives and liberals, with the liberals in the majority. The liberals were particularly concerned about greater transparency in governmental policy. The rural population, which had for centuries constituted the power base of the monarchy, now began to make demands of its own, such as total abolishment of unpaid labour and the right to complete personal freedom. The king resolutely rejected these demands in 1846, sending his traditional allies right into the arms of the liberals. From 1848 to 1919 agriculture was in fact liberalized and freed from the ruling class. This thirst for reform also persisted in trade and commerce, leading to completely free domestic trade, with the old medieval institutions, such as the guilds, abolished. Another victim of this craving for reform was the Sound Toll. Its elimination provided both Copenhagen and the Baltic Sea trade with an enormous boost. One expression of this economic revival was the first Danish train service between Altona and Kiel in Holstein in 1844. The arrival of the modern age was greatly stimulated by the 1839 ascension to the throne of Christian VIII (1786-1848), who was somewhat open to renewal and reform. However, he did not go so far as to allow a Danish constitution. That struggle was to take many more years.

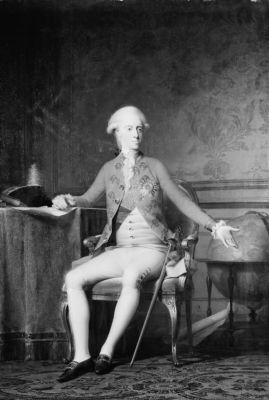

5

Jens Juel

Portrait of Frederik VI (1768- 1839) as crown prince, dated 1786

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KMS797