7. Netherlandish Prints and Religious Art in Denmark

David Burmeister

The topic of this article falls somewhat outside of Horst Gerson’s classic study which, while acknowledging a broader Dutch cultural influence on Denmark, focused primarily on the high quality of production, not least King Christian IV’s decorative projects and the work of artists associated with the court. The Dutch and Flemish artists who were attracted to the country by the Danish kings Frederick II and Christian IV as well as the significant royal purchases of foreign, frequently Netherlandish, art are traditionally seen as the key factors in adapting to international artistic standards in Denmark during the 17th century.1 However, Netherlandish influences on Danish cultural production were equally significant outside the court, especially in the churches.

Following the Reformation in Denmark in 1536, the most pressing matters had been to define the new liturgy and implement and consolidate the new faith throughout the country. Refurnishing the buildings in accordance with the new requirements had to wait and was only truly initiated in the century following ca. 1570.2 But from then on virtually every church in Denmark was fitted with new pews, pulpits and altarpieces and thus played a key role in making both the renaissance style and, from c. 1630, the auricular baroque commonplace in every town and village. While religious imagery was no stranger to the fittings of the late 16th century, its role increased considerably following the advent of Lutheran orthodoxy around 1600, as religious images began to be viewed as important means to assist the believer’s personal spiritual experience.3 To produce these works of art, the painters and wood carvers relied on architectural model books, while the numerous images were almost always anchored in the large quantities of Netherlandish prints available in Denmark.4

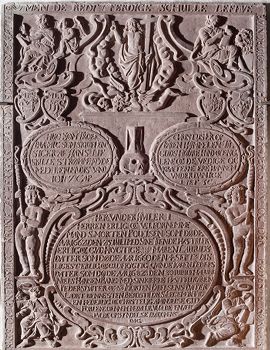

Cover image

Lauritz Riber after Hendrick Goltzius

Sepulchral tablet to Jens Christensen Vamdrup (†1613) with putto blowing soap bubbles (Homo Bulla), dated 1599

Kolding, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Kolding)

The refurnishing projects virtually transformed the interior of Danish churches during the 17th century. A person entering St Nicholas Church in Middelfart towards the end of the century would be surrounded by new imagery of Netherlandish pedigree. Walking to one’s seat and subsequently while approaching the altar to participate in the Communion, the worshipper would have passed several new gravestones embedded in the floor of the central aisle as well as two spectacular epitaphs [2-3], which were all decorated with images of the resurrected Christ designed originally by Maerten de Vos [1].5 Furthermore the brand new staircase for the pulpit [4] was the home of figures of the apostles based on prints by Jacques Callot as well as Antonius Wierix after Ambrosius Francken, while the visual center of the room, the altarpiece of c. 1650 [5], was virtually overflowing with images copied from Netherlandish prints.6 These images served to assist and shape each believer’s individual experience of faith and also contributed to the understanding of one’s place in society. Furthermore, they played a crucial role in the indication of social status, as the lavish decoration of gravestones, pulpits and epitaphs were important markers of the donor’s place in the local community.

1

Crispijn de Passe (I) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Crispijn de Passe (I)

The Resurrection of Christ

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-2196

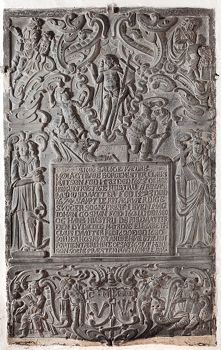

2

Anonymous Denmark c. 1662 after Hieronymus Wierix after Maerten de Vos (I)

Epitaph for Morten Poulsen (†1662) and his wives Maren Lauridsdatter (†1660) and Karen Pedersdatter (†1682), c. 1662

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart), inv./cat.nr. Epitaph no. 1

3

Anonymous Denmark 1691

Epitaph for Mayor Claus Madsen (†1653 ) and his wife Anna Rasmusdatter (†1674 ), and for vicar Johan Gosmann (†1680) and his wife Elisabeth Clausdatter (†1680 ), 1691

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart), inv./cat.nr. Epitaph no. 2

4

Hans Nielsen Bang after Jacques Callot and after Antonius Wierix (II) after Ambrosius Francken (II)

Stairs of the pulpit of the Sankt Nikolaj kirke at Middelfart (Denmark), dated 1675

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

5

Anoniem Anonymous and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

Handcarved altarpiece (frame, c. 1650) with paintings by C.W. Eckersberg: The story of the

great and the small (main section) and Three cupids (top section) both from 1842, c. 1650 and 1842

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

The present article seeks to survey the importance of Netherlandish prints and, in particular, the role of Northern Netherlandish printmakers for the religious art of Denmark. Following an initial survey of the current state of research, I will examine some general trends in the use of Netherlandish engravings in the production of religious art in Denmark. Hendrick Goltzius will play a central role in the analysis, as he has traditionally been considered pivotal to the introduction of Netherlandish Mannerism in Denmark. Based on an analysis of the findings published in the more recent volumes of the corpus on the culture of the church, Denmark’s Churches (1933- ), I will attempt to understand how Goltzius’ prints were used in the art of the churches in comparison with the prints of other key printmakers.7 Furthermore, the role of Dutch 17th-century publishers in the redistribution of 16th-century religious prints will be examined. The use of republished 16th-century prints will be illustrated with Lorentz Jørgensen’s altarpiece for St Olai Church in Helsingør from 1664. It will also be central to the final discussion of the different ways Danish artists approached their Netherlandish models in order to create works of art suitable to the Danish church.

Notes

1 Heiberg 1983, p. 7; DaCosta Kaufmann 2011 pp. 38-44. A survey of the royal acquisitions of art during the first half of the 17th century is provided by Heiberg 2007, pp. 231-244.

2 De la Fuente Pedersen 1998, pp. 39-40. De la Fuente Pedersen does not analyze the decades following 1647, but the material from Funen indicates a considerable increase in the acquisition of new pulpits and altarpieces in this period; often prompted by the desire to replace the renaissance furnishing of the early 17th century with new furnishing in the auricular baroque style.

3 De la Fuente Pedersen 1998, p. 199. On the theological understanding of images in the late 16th century, see Hansen/Bøggild Johannsen 1993, pp. 181-198.

4 See Eller 1974, in particular pp. 9-16.

5 Bertelsen/Kristiansen/Burmeister Kaaring 2010, pp. 2340-2341, 2358, 2359 and 2360.

6 Bertelsen/Kristiansen/Burmeister Kaaring 2010, p. 2310.

7 The publications of Denmark’s Churches are available online via www.danmarkskirker.natmus.dk .