7.3 Comparison to Other Major Printmakers

Although Goltzius’ prints must have been widely distributed in Denmark and used by artists throughout the country, it is not possible to conclude, that they were more readily available than other prints or that they influenced Danish religious art more than other large scale print publishers. Goltzius was certainly not the only Northern printmaker, whose prints reached Denmark. For instance, his pupil, Jacques de Gheyn II, left a solid mark through his series such as Christ, The twelve apostles and St Paul with the creed engraved in 1591-1592 after Karel van Mander I’s inventions (New Holl. 72-85) [1-3], which became rather common around 1625.1

1

Anonymous Denmark dated 1675 after Jacques de Gheyn (II) after Hendrick Goltzius

Lattice from Alderman Christen Nielsen Thonboe's Chapel at Horsens Klosterkirke (Denmark), dated 1675

Horsens, Horsens Klosterkirke

2

Jacques de Gheyn (II) after Karel van Mander (I) published by Jacques de Gheyn (II)

Saint Peter, 1591-1592

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-10.009

3

studio of Hendrick Goltzius and possibly Jacques de Gheyn (II) after Hendrick Goltzius published by Hendrick Goltzius

Saint Paul, 1589

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-10.226

The religious prints of the De Passes were hugely important to Danish religious art as well, and prints such as Magdalena de Passe’s Last Supper (Holl. 3) are known from altarpieces throughout the country [4-5],2 while Crispijn de Passe’s Crucifixion (Holl. 159) has been identified as the model for two altarpieces of 1645 and 1647 in Ribe County.3 The De Passes are among the publishing dynasties, whose contribution to Danish religious art is certainly underrepresented in Denmark’s Churches due to the lack of fully illustrated catalogues on their work, but specialized studies have shown that major workshops such as Jørgen Ringnis’ in Maribo, Brix Michgell’s in Roskilde and Abel Schrøder’s in Næstved regularly copied their prints.4 More recent publications of Denmark’s Churches seem to confirm this widespread use of their prints. We can only speculate to the role of Simon de Passe, engraver to the Danish king from 1624-1647, in distributing De Passes’ prints in Denmark. Considering the firm’s international orientation, it would seem likely that Simon, who long stayed associated with his father’s business,5 would have distributed the dynasty’s prints in Denmark. On the other hand, Simon does not seem to have been particularly interested in obtaining his share of his father’s copperplates upon the latter’s death in 1637, which would perhaps indicate that the redistribution of the family’s prints would at best have been a minor issue to Simon.6

4

Anonymous Denmark c. 1650 after Magdalena van de Passe

The Last Supper, c. 1650

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

5

Jørgen Ringnis after Magdalena van de Passe

The Last Supper, c. 1640-1650

Falster (island), Gundslev Kirke

In order to understand Goltzius’ and De Gheyn’s influence on Danish religious art it is important to remember that they published relatively few biblical narratives and were mainly copied for their single figure prints of virtues, apostles and evangelists. As for Biblical narratives, Danish artists primarily relied on prints of Southern Netherlandish printmakers more specialized in religious imagery than Goltzius and De Gheyn. What mattered was evidently not the identity of the designer or printmaker, but rather the subject matter. The Sadeler brothers’ prints were as frequently copied and Goltzius’, not least Johann Sadeler I’s print of The Last Supper after Peter de Witte I (Holl. 206)7 and Aegidius Sadeler’s print after Hans von Aachen’s Crucifixion (New Holl. 25) [6-8]. And, although the recognition of Maerten de Vos’ importance to Danish religious imagery of the 17th century has only been recognized rather late, prints after his designs were still among the most popular models for Danish artists.8 Indeed, this supremely prolific artist provided Danish artists with models for more biblical histories than any other 16th-century artist.

It is remarkable that the prints after De Vos and other contemporary Antwerp artists only gained widespread use in Denmark around the middle of the 17th century. This must be seen as a consequence of the church’s growing demand for images throughout the century, and as such does not indicate that Antwerp prints were only available some decades after their initial publication. Nevertheless, it strongly suggests that most Danish artists did not work from the by then 60 to 80 years original publications, but rather from later reissues if not from copies. This is particularly interesting in the context of the Dutch influence on Danish art of the 17th century, as many of the plates for popular 16th-century Antwerp print series were by then owned by Northern print publishers. In particular Claes Jansz. Visscher was seminal to the popularization of the Antwerp printing traditions during the first half of the 17th century. In 1612 he had contributed to the so-called ‘Bruegel Renaissance’ of the day by reissuing copies of the famous Small Landscapes with an attribution to Pieter Bruegel, and, from the late 1630s, he was a leading figure in the refashioning of late 16th-century religious prints from Antwerp.9

6

attributed to Jens Olufsen and Sten Adamsen and Hans Bølling after Johannes Sadeler (I) after Peter de Witte (I)

Altar piece from Janderup church (Denmark) with the last supper in the centre, dated 1645

Janderup, Janderup Kirke

7

Johannes Sadeler (I) after Peter de Witte (I)

The Last Supper

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-5320

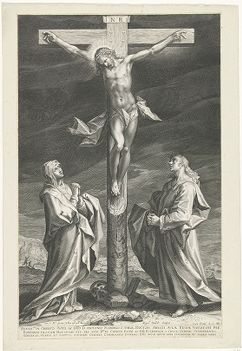

8

Aegidius Sadeler (II) after Hans von Aachen

The crucifixion

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-5104

Notes

1 Frederiksborg Slotskirke (17th century, Danmarks Kirker. Frederiksborg Amt 3, Copenhagen 1970, 1770); Frederiksborg Slotskirke (1606, Danmarks Kirker. Frederiksborg Amt 3, Copenhagen 1970, 1916); Horne (ca. 1625, Danmarks Kirker. Ribe Amt 3, Copenhagen 1988-91, 1461); Grundfør (1630, Danmarks Kirker. Aarhus Amt 4, Copenhagen 1980, 1664); Jørlunde (1640, Danmarks Kirker. Frederiksborg Amt 4, Copenhagen 1975, 2270); Horsens Vor Frelsers Kirke (1670, Danmarks Kirker. Aarhus Amt 10, Copenhagen 2004-05, 5522); Horsens Klosterkirke (1675, Danmarks Kirker. Aarhus Amt 10, Copenhagen 2004-05, 5947).

2 Cf. De la Fuente Pedersen 1998 , p. 196 and below.

3 Janderup Church (Danmarks Kirker. Ribe Amt, Copenhagen 1984, p. 1046) and Billum Church (Danmarks Kirker. Ribe Amt, Copenhagen 1984, p. 1086).

4 De la Fuente Pedersen 1998, pp. 198-199. As for Riber, see: Bergild/Jensen 1991, pp. 98-103.

5 Veldman 2001, pp. 254-258.

6 Veldman 2001, pp. 319-320.

7 De la Fuente Pedersen 1998, pp. 82-83, 185-186.

8 The identification of Danish works of art modelled on De Vos’ inventions only began to appear following the publication of Mauquoy-Hendrickx 1978-1983. A more comprehensive investigation into the use of prints in the churches of Assens, Middelfart and Bogense on Funen has indicated that prints after Maerten de Vos were indeed very commonly copied, see also below.

9 As noted by Schuckman 1990, p. 69.