7.5 Putting Theatrum Biblicum to good use

The use of Visscher’s Bible can perhaps best be illustrated through Lorentz Jørgensen’s monumental altarpiece for St Olai in Helsingør of 1664 [1]. The lavishly decorated altarpiece consists of four tiers containing no less than 19 reliefs and a host of figures, notably putti holding the instruments of martyrdom, the evangelists, St John and Moses. The central axis of the altarpiece consists of three large reliefs of The Last Supper [2], The Resurrection [3] and The Ascension [4] as well as smaller reliefs of Christ washing the feet of St Peter, The entry into Jerusalem and The Entombment above. The three large reliefs follow the same pattern Jørgensen’s used in several altarpieces and are variants of the models used by his master, Hans Gudewerdt II.1 It has not been possible to identify a printed model for Gudewerdt’s and Jørgensens’ compositions, except that the latter in The Ascension included figures borrowed from Johann Sadeler’s engraving after Maerten de Vos (Holl. 1159) [5] and possibly also the feet of Christ from a second version by De Vos (Holl. 506) [6]. This latter print was published first in De Jode’s Thesaurus and subsequently in Visscher’s Theatrum Biblicum.

1

Lorents Jørgensen after Johannes Sadeler (I) and after Antonius Wierix (II) and after Hieronymus Wierix after Maerten de Vos (I)

Altarpiece from the Saint Olai Church at Helsingør (Denemarken) with Scenes from the Life of Christ, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

2

Lorents Jørgensen

The Last Supper, detail of altarpiece of 1664 in Saint Olai Church, Helsingør, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

3

Lorents Jørgensen

The Resurrection, detail of altarpiece of 1664 in Saint Olai Church, Helsingør, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

4

Lorents Jørgensen after Johannes Sadeler (I) and after Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I)

The Ascension, detail of altarpiece of 1664 in Saint Olai Church, Helsingør, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

5

Johannes Sadeler (I) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Johannes Sadeler (I)

The Ascension of Christ, 1585-1588

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1966-83

In an article of 2001 Eva de la Fuente Pedersen identified the primary models for the small reliefs as two Passion series after Maerten de Vos, one that was published in Gerard de Jode’s Thesaurus and the Van Luyck Passion of Christ mentioned above.2 For that reason De la Fuente Pedersen saw an Antwerp connection in Jørgensen’s altarpiece.3 By the time Jørgensen copied the series, the original Antwerp publications were, however, close to 80 years old, and the copper plates for both series had been acquired by Claes Jansz. Visscher and included in Theatrum Biblicum. The combined use of these two series, originally published separately, strongly suggests that Jørgensen’s primary source for the altarpiece was Visscher’s Bible, although he also relied on a few other prints, notably De Vos’ The Descent from the Cross (Holl. 432) [7] and Willem van Swanenburgh’s The road to Calvary after Joachim Wtewael (Holl. 33) [8]. Evidently, rather than proving a connection to Antwerp, the extensive use of Flemish prints in the creation of the altarpiece is yet a reflection of the strong Dutch influence on Danish art during the 17th century.

The altarpiece is interesting for the handling of the models. First of all, it is noticeable that Jørgensen was keenly aware of style and chose models from different sources, both Theatrum Biblicum as well as loose prints that were stylistically related. He relied on a number of individual prints that were designed by De Vos and as such would be in harmony with the prints of Theatrum Biblicum, but even the addition of Wtewael’s composition is carefully coordinated to match De Vos’ figures and narrative structure. Jørgensen’s combination of several prints after De Vos published in both Theatrum Biblicum and elsewhere, and his careful selection of Van Swanenburgh’s stylistically related print confirms the general impression, that Netherlandish prints were readily available to Danish artists, and further seems to suggest that for Jørgensen the use of late 16th century Mannerist prints was a deliberate choice.

6

Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Gerard de Jode

The Ascension of Christ, 1585

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1988-312-325

7

Johannes Sadeler (I) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Johannes Sadeler (I)

The Descent from the Cross, 1583

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1966-75

8

Willem van Swanenburg (I) after design of Joachim Wtewael published by Christoffel van Sichem (I)

Christ carrying the Cross, 1606

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-60.824

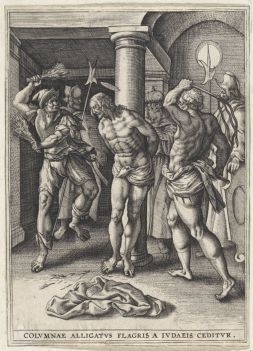

Secondly, Jørgensen’s approach to his models tells us something about the different ways Netherlandish prints could be used to express a Lutheran understanding within the context of a Danish church. In two cases he combined two prints to form a new image. He replaced one tormentor holding two scourges in The Flagellation [9] with an almost identical [10-11], but frontal figure from another engraving by De Vos (Holl. 637), and in The Crowning with Thorns he combined figures from the two prints from De Jode’s and Van Luyck’s aforementioned series [12-14]. Although it is not entirely clear what Jørgensen hoped to achieve by swopping one tormentor for another, we may perhaps find a clue in The Crowning with Thorns. Here Jørgensen seems to have sought a frontal depiction of Christ and for that reason opted for the figure of Christ from Van Luyck’s print, but placed it in De Jode’s composition. De la Fuente Pedersen has stressed that Jørgensen opted to place focus on Christ by placing him frontally at the center of the main axis’ reliefs, while also adapting The Entombment in order to show the dead body of Christ frontally. Probably his approach to the reliefs of The Crowning and The Flagellation are further examples of this minor adjustment of the models to form a unified whole in the altarpiece.

9

Lorents Jørgensen after Antonius Wierix (II) and after Hieronymus Wierix after Maerten de Vos (I)

The Flagellation, detail of altarpiece of 1664 in Saint Olai Church, Helsingør, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

10

after Maerten de Vos (I)

The Flagellation, 1560-1600

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-68.133

11

Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Hans Liefrinck (I)

The Flagellation, 1586-1590

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1906-2090

While Lorentz Jørgensen was able to rely on tried and tested models for the main reliefs of the central axis, the size of the altarpiece required him to add additional imagery, which he found primarily in Visscher’s Bible. As we have seen, he copied these rather faithfully, with due considerations to the flexibility of the wood and with slight moderations to establish a coherent and unified whole across the many reliefs. Although the individual reliefs were barely altered, they were orchestrated to form a unified and pregnant whole centering on the large relief of The Last Supper. This relief was adapted from Jørgensen’s master, Hans Gudewerdt, so as to stress the liturgical offering of bread and wine through the two figures seated in front of the table: Judas by receiving the morsel of bread, while the disciple to the left holds up a chalice deceptively similar to the one acquired by the church only a few years earlier.

Thus, just as in the case of Goltzius’ print, the communicant kneeling before the altar would be faced with a work of art, which was to stress both the mimetic connection to the rite performed and to make clear the Lutheran understanding of the Eucharist. At the basic level it stressed the importance of administering both the bread and the wine but, on a deeper level, the mimetic re-enactment of The Last Supper would make evident Christ’s Real Presence that, with the reading of Christ’s words, he would be present in the water and wine.4 Hence the communicant would be encouraged to understand the central axis of the altarpiece culminating in the reliefs of The Resurrection and The Ascension not only as a representation of the key events of the Passion, but as a reminder that participation in the Eucharist was an acceptance of a life in Christ that would ultimately lead to salvation. This central axis is elaborated by the many secondary images. For instance, the Passion reliefs surrounding the central axis elaborates on the nature of Christ’s offer to Man in the Eucharist and can in that respect perhaps be understood as a reference to the doctrine ‘Solus Christus’, that Christ alone redeems Original Sin, just as the large sculptures of the evangelist obviously hint at a second doctrine ‘Sola Scriptura’, that the Bible is the only authoritative word of God and accessible to everyone.

12

Lorents Jørgensen after Antonius Wierix (II) and after Hieronymus Wierix after Maerten de Vos (I)

The Crowning with Thorns, detail of altarpiece of 1664 in Saint Olai Church, Helsingør, 1664

Helsingør, Sankt Olai Kirke

13

after Maerten de Vos (I)

The Crowning with Thorns, 1560-1600

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-68.134

14

Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Gerard de Jode

The Crowning with Thorns, c. 1585

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1988-312-314

Notes

1 Behling 1990, fig. 17-22.

2 De la Fuente Pedersen 2001, pp. 151-152. With a slight correction of De la Fuente Pedersen’s identifications, the reliefs copies the two series as follows: The Adoration of the shepherds, The entry into Jerusalem, The washing of Christ’s feet and The Entombment are all copied after De Jode’s Thesaurus, whereas The Arrest in the Garden, Christ before Caiaphas, Christ before Pilate and Pilate washing his hands were copied from Van Luyck’s Passion series. Two further reliefs which combined two prints will be discussed later.

3 De la Fuente Pedersen 2001, p. 152. De la Fuente Pedersen also mentions that Claes Jansz. Visscher reissued Van Luyck’s Passion, but as she mistakenly considers him an Antwerp publisher (cf. also De la Fuente Pedersen 1998, p. 81), this is pointed out to confirm the Antwerp connection.

4 On the connection between representations of The Last Supper in altarpieces and the communion rites, see: Wangsgaard Jürgensen 2013, pp. 74-88.