7.6 Common Approaches to Printed Models

The Helsingør altarpiece exemplifies a number of ways Danish approached Netherlandish models. First of all, even in cases where a specific print’s model has not been identified, the Danish religious artworks are likely to reflect the same iconographical traditions and compositional and narrative devices as we find in Netherlandish prints. In these cases one often wonders whether the Danish work of art was based on a lost print or was simply inspired by the solutions the artist knew from his portfolio of prints. A related approach was to merge elements from two or more prints into a new composition. As we have seen, this was often done without any apparent changes to the iconography, perhaps for the sake of visual unity within the new work of art. Another popular approach was exemplified by Jørgensen’s alteration of his master’s model for The Last Supper. Here the model was altered to accentuate a culturally specific interpretation. Other times the prints were perfectly acceptable in a Lutheran context, and could simply be adapted to the new medium. This was the case with the majority of De Vos’ Passion prints. In other cases, the Netherlandish images were suited to express a specific religious understanding in the context of an altarpiece. For instance, the overwhelming presence of The Last Supper on Lutheran altarpieces, while not in itself denoting a specific confession, can still be said to reflect Luther’s recommendations for retables. In cases such as Goltzius’ popular handling of The Last Supper, within the context of a Lutheran altarpiece it could express the importance of administering the wine as part of the re-enactment that would make Christ present and graspable.1

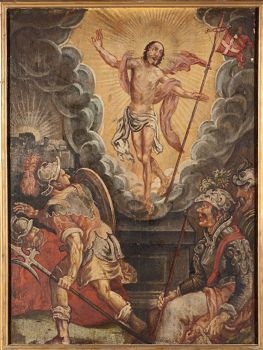

Finally, a very common approach to the printed models was to imbue inter-confessional imagery with a Lutheran meaning not through the alteration of individual models, but through the orchestration of several prints into a new and meaningful whole. This approach was hinted at in the analysis of the St Olai altarpiece, but is perhaps even more evident in the original appearance of the aforementioned altarpiece of Middelfart Church of c. 1650 [1-2] which includes copies after masters such as Goltzius, Guilio Clovio (through Cornelis Cort’s print [3]) and Maerten de Vos. In the original appearance the central axis of the altarpiece would have consisted of a relief of The Last Supper, paintings of The Crucifixion (lost) and The Resurrection (removed) and finally a sculpture of The Last Judgement. These images are obviously not specific to Lutheranism, although they do reflect a typically Lutheran choice of motifs. However, what imbues a specifically Lutheran meaning to the altarpiece are the two figures of Christ and Moses placed in in niches at the sides of the central painting, the former incidentally copied after a De Vos print included in Theatrum Biblicum [4]. By placing figures of Faith [5] and of Charity on the altarpiece’s left side near Christ and Justice and Hope [6] at Moses’ side, the typically Lutheran theme of Law and Gospel is established. Thus the combination of images expresses the Lutheran understanding that the Law makes man aware of his sins, but what saves him is the faith in Christ that is announced in the Communion rite performed before the altar. Thus while the images are rather faithful copies of confessionally neutral imagery, they are combined to expresses central Lutheran understandings of both the character of the Old and the New Covenant and their mutual relationship.

The production of religious images in Denmark reached new heights during the 17th century. As we have seen, these images were highly dependent on imported prints both for general knowledge of Early Modern religious iconography and as concrete models for their works of art. Indeed, with some justice it has been stated that independent compositions were very rare in Denmark during this period.2 As we have seen, within the context of religious works of art, the majority of the models were Netherlandish prints originally published in the decades leading up to 1600, but republished and readily available throughout the 17th century. The inventions of Dutch printmakers such as Hendrick Goltzius, Jacques de Gheyn and the De Passes were hugely important to Danish artists, who made particularly good use of their many single figure representations of the Virtues, Evangelists and Apostles. Although the frequent use of Goltzius’ inventions was confirmed, it is clear that Danish artists were mainly concerned about the subject matter and relied extensively on Southern Netherlandish models for their biblical histories. Nonetheless, I have argued that the republishing in the 17th century by Dutch publishers and in particular by Claes Jansz. Visscher was crucial to the popularity of late 16th-century Antwerp prints in Denmark after c. 1650. The popularity of 16th-century religious prints in Denmark must, then, be understood not as a sort of belatedness, but rather as a reflection of the prints’ ongoing importance in the 17th-century market for religious works of art, and of the 17th-century Dutch revival of Flemish artistic traditions.

The popularity in Denmark of religious prints produced in 16th-century Antwerp can perhaps be seen as a result of their usefulness for the Lutheran orthodoxy that came to dominate in Denmark during the 17th century. Following the Beeldenstorm in 1566 religious imagery was passionately debated in Antwerp and artists had to carefully manoeuver within the many differing views on religious matters as well as on the status of images. A very common approach to the problem was to adhere strictly to Scripture and create images that would be acceptable across confessions, while perhaps particularly appealing to a specific denomination.3 Such images were likely to be readily acceptable and their subject matter even perfectly suited to the Lutheran orthodoxy with its preference for illustrations of the second article of The Apostle’s Creed, the belief in Christ, his sufferings and resurrection, and the two sacraments Luther acknowledged, as they were mentioned in the Gospels: Baptism and Communion.

1

Anoniem Anonymous and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

Handcarved altarpiece (frame, c. 1650) with paintings by C.W. Eckersberg: The story of the

great and the small (main section) and Three cupids (top section) both from 1842, c. 1650 and 1842

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

2

Anonymous Denmark c. 1650 after Cornelis Cort after Giulio Clovio

The Resurrection of Christ, c. 1650

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

3

after Cornelis Cort after design of Giulio Clovio

The Resurrection of Christ, after 1569

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1888-A-12483

4

Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I) published by Claes Jansz. Visscher

Christ showing his wounds

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1904-170

5

Anonymous Denmark c. 1650 after Antonius Wierix (II) after Maerten de Vos (I)

Christ with the Cross and personification of Faith, c. 1650

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)

6

Anonymous Denmark c. 1650

Moses with the Tablets of Law and a Personification of Hope, c. 1650

Middelfart, Sankt Nikolaj Kirke (Middelfart)