3.5 Court Art at the Time of Karel van Mander III

Following the premature death of her husband, Karel van Mander II’s widow left with her brother, the painter Engel Rooswijk (1583/84-1642/49), and her children for Copenhagen because she was still owed money by the King. She started a grocery business opposite the castle.1 Her eldest son, Karel van Mander III (1609-1670), became the most important court painter of the new generation.2 In 1630 he received his first canvas for painting a portrait of Christian IV. More commissions followed, not only for the King but also for the Prince Elect Christian, for whom he painted full-length portraits in 1631.3 In 1634 both Simon de Passe and Karel van Mander III received the commission to design the decor for the court ballets that were performed during the festivities around the marriage of the Prince Elect Christian and Magdalena Sibylla of Saxony. Never before had a marriage been celebrated in Denmark on such a grand scale and with so many foreign guests. 4

In 1635 Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656) supplied a series of four ceiling paintings with themes based on the at that time popular Aethiopica by Heliodorus for the King’s Chamber at Kronborg. A fire had ravaged this castle in 1629, making a partial rebuilding and restoration necessary. The ceiling paintings were made in the Republic and shaped in situ into trefoil-shaped panels, surrounded by four tondi with the monograms of the royal couple, the parents of Christian IV and those of the newly married Prince Elect Christian and his wife. The theme of the Aethiopica was extremely popular in Denmark, probably because it was related to the theme of the hereditary monarchy.5 In Denmark the successor to the throne was elected by a council of noblemen. It was not until the reign of Frederick III that the monarchy became hereditary.6

In 1635 Karel van Mander III asked the King permission to make a study trip. With financial support from Christian IV he then left for Rome, via the Republic, the Southern Netherlands and Paris. He was back in Copenhagen by June 1639 at the latest.7 In the years that Van Mander III was abroad, new developments occurred in Copenhagen. Van Mander’s uncle Engel Rooswijk had returned to Copenhagen, where he painted the majestic full-length portrait of Corfitz Ulfeldt (1606-1664), the son-in-law of Christian IV [1]. In May 1640 Rooswijk provided the King himself with four portraits. A short while later he travelled by ship to Amsterdam, with a sum of money from the King and Prince Christian to purchase paintings. The ship was hijacked by Dunkirk pirates and the King was forced to ask the Spanish governor in Brussels to intervene.8

1

Engel Rooswijk

Portrait of Corfitz Ulfeldt (1606-1664), husband of Leonora Christina, daughter of King Christian IV and Kirsten Munk, dated 1638

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. A 833

In the period between 1635 and 1639, the Haarlem painter Adriaen Muiltjes (1601-1647) was working in Copenhagen, at first as assistant to Morten van Steenwinckel, and later as an independent painter [2].9 He married the daughter of a Dutch merchant from Helsingør. In 1637 he was given permission by Christian IV to publish prints of Kronborg. From Morten van Steenwinckel’s studio we know the names of two pupils as well: Bartholomæus Spitzmacher (active before 1639-1668) and Bernard Keil (1624-1687), the son of an artist in Helsingør. Spitzmacher travelled to the court of the Swedish Dowager Queen in Nyköping on behalf of Van Steenwinckel.10 Keil became a pupil of Rembrandt’s from 1642-1644 and worked for the art broker Hendrick Uylenburgh from 1645-1648; from 1649-1651 he had his own studio in Amsterdam before in 1656 he left for Rome, where he was to remain until his death.11 Morten van Steenwinckel, who is described on his tombstone as ‘architect and painter in the service of the Prince’, went on to become an exceptional painter of horses, for which – partly thanks to his pupil Keil – he became internationally renowned [3].12

During Karel van Mander III’s absence, Simon de Passe became the head of a major project: a book with prints on the history of Denmark and the Danish monarchy from its earliest origins. Simon de Passe invited a group of Utrecht artists to produce the drawings. Of these drawings, 43 are still held in the Kobberstiksamling of the Statens Museum for Kunst; more than half were made by Chrispijn de Passe, the brother of Simon, who was in Denmark in 1638 for this commission. The other drawings were made by Honthorst (ten), Abraham Bloemaert, Jan van Bijlert, Nicolaus Knüpfer, Adam Willaerts, Simon Peter Tilman and Antonis Palamedesz (each of whom contributed one drawing). On the basis of a choice from these drawings, paintings were produced for the decoration of the Dance Hall at Kronborg. The paintings arrived in Denmark between 1641 and 1643. At the present time, 17 works from this series are still known: Honthorst painted nine of them, Claes Moeyaert, Isaac Isaacsz and Simon Peter Tilman each made two, Adriaen van Nieulandt and Salomon de Koninck each provided one.13 In 1657-1658, the Swedes confiscated some of these works as spoils of war.14 The book itself was never finished, which caused Simon de Passe to fall into disfavour with the King.

In 1638, Abraham Wuchters (1608-1682) came to Copenhagen.15 In 1639 he became the successor to Reinhold Thim at the Academy for the Aristocracy at Sorø. Wuchters was given a contract for six hours a day, a high salary and a furnished staff residence.16 He was required to teach sketching, drawing and architecture to the young nobles who attended the Academy; an assistant could take his place for three of the six hours so that he himself could devote extra attention to the most gifted pupils. 17 From 1640-1642 he spent some time abroad, while still receiving his salary.18 He spent a period of time in Amsterdam, where he arranged for prints of portraits of the King to be made, but it is unclear what else he was engaged in during these two years. In 1643 the engraver Albert Haelwegh (1620-1673) also came from the Republic to Denmark.19 In 1647 he was to succeed Simon de Passe, both as engraver to the King and to the University of Copenhagen. Haelwegh produced prints of many portraits of both Karel van Mander III and Abraham Wuchters. In 1653 he married a sister of the wife of Abraham Wuchters, thus uniting their families. In 1673 Wuchters succeeded his brother-in-law as royal engraver.20

2

Adriaen Muiltjes

King Christian IV (1577-1648) on horseback, with in the background prince Christian and Kronborg Castle, c. 1635-1638

Copenhagen, The Royal Danish Collection - Rosenborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. 1.130

3

and Morten van Steenwinckel Karel van Mander (III)

Equestrian portrait of King Christian IV (1577-1648) of Denmark, c. 1643

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. A 2741

Following his return to Copenhagen in 1639, Karel van Mander III painted a number of works that clearly show the influence of Rembrandt and his circle, such as the Aaron as high priest that was part of the collection of Count Adam Gottlob Moltke in the 18th century and at that time considered to be by Govert Flinck [4].21 Other works betray the influence of Hendrick Bloemaert, such as the Old woman with flute/Hearing, from a series depicting the Five Senses, dating from 1639 [5]. Like Rembrandt’s, Van Mander’s paintings feature a strong chiaroscuro effect. At times he used the pointed end of the brush to create the effect of relief. This is clearly visible in the hanging part of the old woman’s turban.22

The studios of the Dutch artists in Denmark in the 17th century tended not to be very large; they comprised generally three people, including pupils.23 At the start of his career, Van Mander had one assistant, Jacob, in his service. It is known that in 1645, besides his family, eight men and women lived in his house, but their relationship to the artist is unclear. One of them, Philip Ohm (active 1645-1654), later worked for Charles X Gustav (1622-1660), who recommended his services to architect Nicodemus Tessin I, on account of his broad skills in many different fields.24

4

Karel van Mander (III)

Aaron as high priest, c. 1640

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KMS7985

5

Karel van Mander (III)

Allegory of hearing / An old woman with a flute, 1639

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. Sp. 800

6

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway (1577-1648) with a view on the Sound and Kronborg Castle, first half of the 1640s

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 402924

At the start of the 1640s Karel van Mander III painted portraits of the then roughly sixty-year-old King, that even to the present day determine the public image of Christian IV [6]. The most noticeable difference with the portrait by Wuchters is that Karel van Mander’s portraits emanate a warm, golden glow, while those by Wuchters have a more pearlised and silver palette. Numerous copies have been made of these portraits, where the King is sometimes depicted in civil dress and at other times in military uniform. It is the official portrait made by royal engraver Albert Haelwegh that is most frequently reproduced [7]. After 1644 Karel van Mander III no longer depicted the King in this way. In that same year, during the Torstensson War (1643-1645), Christian IV was struck in his right eye by a piece of shrapnel while on his flagship. From that time onwards the old type of portrait was no longer used and Christian IV was only portrayed in profile, with his face turned to the left, the intention being to remind the viewer constantly of the King’s heroism [8].

7

Albert Haelwegh after Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of King Christian IV (1577-1648) of Denmark, c. 1644-1645

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle

8

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of King Christian IV (1577-1648), en profil with feathered hat, c. 1645

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. A 2545

9

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Leonora Christina (1621-1698), daughter of King Christian IV and Kirsten Munk, c. 1643-1644

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. A 7435

Apart from working for the King himself, Karel van Mander III also made paintings for the Prince Elect and his wife and the daughter of Christian IV, Leonora Christina (1621-1698) and her husband Corfitz Ulfeldt, governor of Copenhagen, who maintained an exceptionally luxurious court. Karel van Mander III was drawing master to Leonora Christina, which she later mentions in her memoirs [9].25

In 1643 Karel van Mander III, together with Morten van Steenwinckel, painted the famous equestrian portrait of Christian IV, of which several copies were produced. The largest version, signed by Karel van Mander III, is hanging in Schloss Eutin in Holstein [10]. In the background horsemen and infantry are leaving under a Danish flag towards a burning city, probably intended to depict Kalmar. The stately, formal style of the horse and horseman can be explained by the fact that Christian IV had for a long time wanted to have an equestrian statue made of himself. The costs involved in such a venture at this time of economic downturn were considered to be inappropriate. Nonetheless, the monarch felt the need to create a reminder of his greatest achievement, even though thirty years had passed since this war.26

10

and Morten van Steenwinckel Karel van Mander (III)

Equestrian portrait of King Christian IV (1577-1648) of Denmark, ca. 1643

Eutin, Stiftung Schloss Eutin

In the early 1640s, Karel van Mander III was prospering. At that time he already had an impressive Kunst- und Wunderkammer.27 He worked not only for the royal family, but also for the aristocracy, for professors, mayors, senior officials and wealthy merchants. Besides portraits, he painted biblical scenes and history pieces. He produced, probably with assistants, a number of large decorative series, of which three still remain: an educational series at Holsteinborg, the Aethiopica series, that is now in Kassel 28 and a series of ceiling paintings with the Five Senses at Amalienborg (originally in a smaller house in the gardens of Rosenborg) from his final period.29 Other series by the artist are mentioned by the Spanish ambassador Count Bernardino de Rebolledo (1597-1676) [11], a close friend of Van Mander. These decorated the hunting lodge Hirschholm (Hørsholm) that belonged to Queen Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Lüneburg, the wife of the new King Frederick III (1609-1670).30

11

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Count Bernardino de Rebolledo (1597-1676), c. 1656

Hillerød, The National Museum of History Frederiksborg Castle, inv./cat.nr. R 203

During the reign of Frederick III (1648-1670), Karel van Mander III - so it seems - received fewer commissions for portraits of the royal family. From 1651, at the request of the King, he was involved in observing the anatomical dissections by physician Thomas Bartholin (1616-1680) [12]. At the start of the fifties, Van Mander bought a large mansion with a courtyard and accommodations for rent on what is currently Strøget, where he amassed his still growing collection and his sizeable library. It was at this residence that, at the request of the King, Van Mander and his wife Maria Fern [13], received for shorter or longer periods ambassadors and other prominent persons from throughout Europe; he was often commissioned by the King to paint portraits of these important guests. For example, in 1656 he produced the unique series of portraits of five Dutch naval heroes, as part of a series of 24 ambassadors for Frederiksborg [14-18]. The portraits of the sea heroes, together with many other works, were removed from the castle by the Swedes in 1658-1660 as spoils of war. To the present day the portraits are exhibited as overdoor pictures at Skokloster, the castle of the Swedish commanding officer Carl Gustav Wrangel (1613-1676).31

13

Karel van Mander (III)

Self-portrait with his wife Maria Fern and his mother Cornelia Rooswijck, c. 1656

Copenhagen, SMK - National Gallery of Denmark, inv./cat.nr. KMS3814

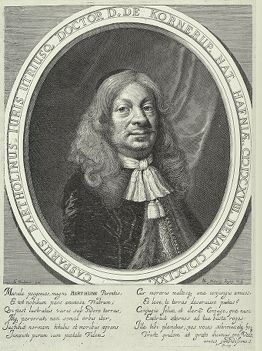

12

Albert Haelwegh after Abraham Wuchters

Portrait of Caspar Bartholin (1618-1670), in or after 1671

Copenhagen, SMK - The Royal Collection of Graphic Art

14

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Jacob van Wassenaer Obdam (1610-1665), 1656

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 1673

16

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Witte Cornelisz. de With (1599-1658), 1656

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 1672

15

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Michiel Adriaensz. de Ruyter (1607-1676), 1656

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 1671

17

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Pieter Florisz (1602-1658), 1656

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 1670

18

Karel van Mander (III)

Portrait of Cornelis Tromp (1629-1691), 1656

Uppsala (province), Skoklosters slott, inv./cat.nr. 1669

In any event, from 1654 on Van Mander was involved in the Kunstkammer of Frederick III, that, together with the library was housed in a new building in 1665, the Museum Regium.32 Towards the end of his life, Frederick III, who was very interested in science, for the first time bought some Italian artworks, including sculptures and paintings, probably encouraged by Peder Schumacher Griffenfeld.33 Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts (active 1657-1675) worked -- possibly after the intervention of Karel van Mander III -- between 1668 and 1672 on the Perspective Room of this new Museum Regium, first under Frederick III, and subsequently under Christian V (1646-1699), who completed his father’s project. This room represented a studiolo, where king and artist worked closely together on gathering, selecting and cataloguing scientific discoveries from throughout the world.34 On New Year’s Day 1670, Karel van Mander III was officially appointed Inspector of the Royal Art Collection by Christian V. The artist died just three months later.

Notes

1 Eller 1971, p. 107, note 16.

2 Recently two studies on Karel van Mander III have been published: Roding 2014 and Lyngby/Mentz/Roding 2015.

3 Eller 1971, p. 109.

4 Wade 1996; Wade 1999.

5 Lassen et al. 1973, p. 210. See Gerson, § 2.5.

6 See the contribution by Jan Kosten, § 1.5.

7 Eller 1971, 111, note 24.

8 Eller 1971, pp. 128, 130-131. See Gerson, § 2.7.

9 Lassen et al.1973, p. 200.

10 Lassen et al. 1973, p. 200.

11 Heimbürger 1988.

12 Beckett 1934.

13 Schepelern/Houkjær 1988; Veldman 1991; Bøggild Johannsen/Johannsen 1993, pp. 130-131; Lange 2011, p. 106-113. All illustrated in Gerson, § 3.5.

14 Some of these works are currently in Östra Ryds Kyrka, Uppland (1), at Skokloster (4) and Drottningholm (1).

15 On Wuchters, see the contribution by Mikael Bøgh Rasmussen, § 5.

16 Eller 1971, pp. 195-196; at the premises built in 1623 there are still two houses for teachers at the Academy. Between 1643 and 1646 Wuchters built a small house, probably for his marriage to Maren Hansdatter, daughter of a vicar.

17 Contract in Friis 1872-1878, p. 148. Eller 1971, p. 197.

18 Eller 1971, pp. 195-196.

19 Sthyr 1965.

20 Sthyr 1965, p. 18 and note 38.

21 See the contribution by Michael North, § 5.5.

22 On Van Manders’ style, see also Gerson, , § 2.11.

23 Bang 1996, vol. 1, pp. 20-21.

24 Eller 1971, pp. 135, 403, 416.

25 Wamberg 1990, p. 56; Waldstein-Wartenburg 2010.

26 Bøggild Johannsen/Johannsen 1993, p. 112; Hein et al. 2006, pp. 56-59.

27 Roding 2006.

28 Stechow 1953; McGrath 1992; Spicer 2010. All illustrated in Gerson, § 2.11.

29 Jespersen et al. 2010; for Morell, see North 2012 and Michael North’ article in this volume, § 6.

30 Gigas 1883, pp. 201, 214-222.

31 Eller 1971, ‘Fem søhaner’.

32 See the contribution by Michael North in this volume, § 6.1.

33 Eller 1971, p. 72 and notes 190 and 191.

34 Bøggild Johannsen/Johannsen 1993, pp. 157-158; Gammelbo 1955; Adang 1971; Braun 1994; Koester/Brusati et al. 1999; Koester 2000; Roding 2001, De la Fuente Pedersen 2003-2004.